by

Damien F. Mackey

What follows is an old article

(originally entitled “Thutmose III as ‘Shishak’”)

here significantly modified.

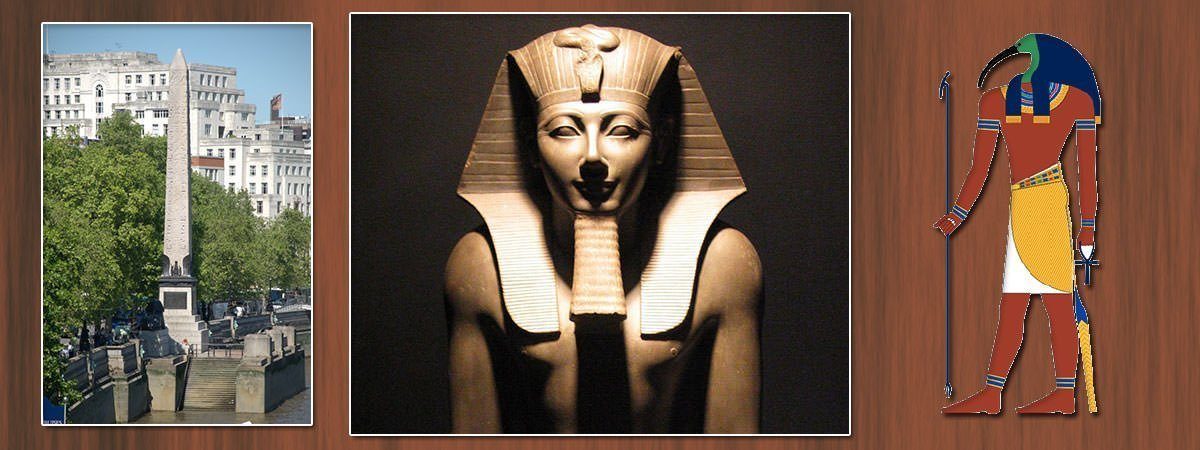

Champollion’s

Shoshenk

as “Shishak”

Jean

François Champollion was obviously a prodigious talent to whom we owe the first

translations of the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs. But he was also a pioneer,

hence susceptible to some early miscalculations. His identification, with

Megiddo, of Thutmose III’s Mkty, was, as far

as Sir Henry Breasted was concerned, as if set in stone.

I wrote this before I had

(most recently) come to accept that the Mkty in the pharaoh’s annals

was meant to intend the strong fort of Megiddo in northern Israel. See my

article on this:

The most

interesting candidates (I think) who have been put forward for the biblical

“Shishak king of Egypt” (I Kings 14:25), are: Shoshenk I; Thutmose III; and

Ramses II.

Shoshenk I, because

he was the choice of Champollion, and because this identification is still, to

this day, purportedly a biblically-based pillar of Egyptian chronology –

namely, the 5th year of Rehoboam, son of Solomon, tied to the 21st

year campaign of Shoshenk I.

Thutmose III, because

he alone is, according to my revision - with his co-ruler Hatshepsut as a

contemporary of Solomon’s (following Velikovsky) - historically appropriate for

“Shishak”.

Ramses

II, who

is David Rohl’s candidate for “Shishak” (A Test of Time:

The Bible - From Myth to History, 1995) - because Rohl presents a very good argument

in support of his case.

Who “Shishak” is not

Dr Elizabeth Mitchell,

who has written for Answers in Genesis an article in which she pleads,

“Will the Real Shishak Please Stand Up?”, has followed this up further on in

the article with the amusing heading (https://answersingenesis.org/archaeology/ancient-egypt/will-the-real-shishak-please-stand-up/):

“Will the

Wrong Shishak Please Sit Down?

So how did this the

chronological confusion come about?

Jean Champollion, the

brilliant translator of the Rosetta Stone, unwittingly gave support to

inconsistent chronology when he erroneously identified Pharaoh Shoshenq as the

Shishak of the Bible. Champollion found an inscription about Shoshenq, founder

of the 22nd Dynasty, at the temple of Karnak. Because the names sound similar,

Champollion assumed that Shoshenq was Shishak. Then, with the biblical date for

Rehoboam as a starting point, chronologists used Manetho’s list to outline the

next three centuries of Egyptian history.

Many Bible scholars have

trusted traditional chronology even when it disputes the Old Testament.

Manetho’s list is problematic

enough, being full of discrepancies, duplications, and overlaps, but the

starting point Champollion thought he’d found was incorrect. The two problems

with identifying Shoshenq as Shishak involve military strategy and phonics.

According to the Karnak inscriptions, Shoshenq attacked the northern part of

Israel, not Rehoboam’s Jerusalem or Judah. As we said earlier, Jeroboam was

Shishak’s friend and probably his ally. If Shoshenq were Shishak, then Shoshenq

attacked his friend and ignored his enemy. Furthermore, the phonetics of these

two pharaohs’ names only sound similar in transliterated form, not in the

original languages.

Because of this faulty

identification of Shoshenq with Shishak, Egyptologists ignored the rest of the

biblical facts relating to the geography and characters involved. Then, because

dates determined by combining the Shoshenq-Shishak error with a misplaced

acceptance of Manetho’s work almost magically match traditional information

about the confusing Third Intermediate Period, many Bible scholars have trusted

traditional chronology even when it disputes the Old Testament.

We should take a lesson from

this bit of history.

Champollion, with the best of

intentions, a brilliant mind, a track record for great discoveries, and a

belief in biblical history, stumbled. He began with the Bible and developed

what seemed to be a perfect match. But when further analysis produced

discrepancies with the Bible, the biblical Egyptologists of the time dropped

the ball. They held on to their original interpretations of the evidence even

when it forced clear discrepancies with the Bible.

In creation ministry, we also

sometimes discover that models or arguments once popular among Christians, when

examined more closely, actually conflict with new discoveries or, even more

importantly, with Scripture. This website even maintains a section of

arguments

creationists should avoid. All evidence needs to be viewed through biblical

glasses. We need to always be like the Bereans, who were commended because they

“searched the Scriptures daily” (

Acts

17:11), measuring all we “know” according to God’s Word and not

being too stubborn to change any unscriptural ideas we may have.

[End of quote]

Professor James

Henry Breasted considered the warlike Eighteenth Dynasty pharaoh, Thutmose III

(c. 1480-1425 BC, conventional dating), to have been “the Napoleon of Egypt” (Ancient

Times, I, Ginn and Co., 1914, p. 85). Now, Thutmose III has been

confidently dated according to the ‘Sothic’ scheme of things to the C15th BC.

Dr. Eva Danelius gives a brief summary of this astronomical scheme in her

article, “Did Thutmose III Despoil the Temple in Jerusalem?” (SIS Review, Vol.

II, No. 3, 1977/78, pp. 64-79). She wrote:

The scheme commonly applied is

that of a calendar tied to the fixed star called Spdt in Egyptian,

Sothis in Greek, and Sirius by the Romans - the English "Dog Star".

The star becomes visible in Egypt about the time when the Nile begins to rise -

the most important event for a country the productivity of whose fields

depended on the annual Nile Flood. After having tied the calendar to a fixed

star, it became possible, through most complicated mathematical and

astronomical observations and operations in combination with Egyptian texts, to

secure so-called "astronomically fixed dates" for some pharaohs. In

this way the reign of Thutmose III, including that of Thutmose II and Queen

Hatshepsut, was "astronomically fixed" as from May 3, 1501 to March

17, 1447 BC ….

[End of quote]

For a more detailed analysis of the

Sothic dating method, see e.g. my article:

The Fall of the Sothic Theory:

Egyptian Chronology Revisited

This artificial ‘Sothic’

system has yielded (as we have already learned) wildly inaccurate dates for

Eighteenth Dynasty figures such as Hatshepsut and Thutmose III, who were, in

actual fact, approximately C10th BC figures.

Ramses II and

his fellow Nineteenth Dynasty Egyptian rulers have also been well mis-dated.

(And yet biblical historians try to tie Ramses II to the Pharaoh of the

Exodus).

For a suggested

revised era for Ramses II, see my article:

New Revision

for Ramses II

The 22nd

dynasty’s Shoshenk I, accorded a C10th BC location, conventionally speaking, is

to be dated significantly later than this.

By far the

majority of scholars are prepared - with so much seemingly weighty scientific

argument behind the Sothic theory - simply to fall into line with its

chronological conclusions. And so these would not quibble with the blatant

conclusion of Professor Breasted that Thutmose III’s First Campaign, in

his 22nd-23rd Year, occurred during April/May of 1479 BC.

A record of the

pharaoh’s many campaigns, including this first one, have been inscribed upon

the wall of the Temple of Amun.

… around 1437 BC, Thutmosis

[Thutmose] had the story of his campaigns in Syria and Palestine inscribed on

the walls of one of the sanctuaries of the great temple of Amun at Karnak.

At the beginning of the first horizontal line that

stands at the top of the wall, one can read the pharaoh’s dedication of this

inscription to Amun: “His Majesty commanded that there be recorded on a stone

wall in the temple he had renovated ... the triumphs accorded him by his

father, Amun, and the booty he took. And so it was done.

Moreover:

The narrative is organized by

year (hence the name "annals"), and each entry gives the course of

the campaign, together with accounts of booty brought back and of the

supposedly voluntary tribute paid by Nubia and by various countries of the Near

East in recognition of the pharaoh's might.

According

to Breasted, the ‘Napoleonic’ pharaoh, in the 22nd year of

his long reign (54 years), embarked upon a military expedition into Syria, in

order to fight against a coalition of Syrian princes under the leadership of

the “King of Kd-šw”, who had revolted against Egypt.

Kd-šw

has been identified as the city of Qadesh, or Kadesh.

Pharaoh Thutmose

III emerged from this campaign with a great victory and immense spoils from the

conquered territories. Dr. Eva Danelius takes up the story, and how Megiddo got

into the picture (“Did Thutmose III Despoil the Temple in Jerusalem?”, SIS

Review, Vol. II, No. 3, 1977/78, pp. 64-79):

… the greater part of

Thutmose's report is dedicated to the fight for a city My-k-ty (now

read Mkty), its siege and final surrender. In their search for a city

written this way in hieroglyphs, Egyptologists decided that My-k-ty

must be the transcription of the name Megiddo, a city in the Plain of Esdraelon

well known from the Old Testament.

…. According to common

consent, Thutmose III was the first pharaoh to conquer Megiddo.

Regarding

Champollion’s identification of “Shishak” with Shoshenk I, Dr. J. Bimson, in

1986, would turn this right on its head in his article, “Shoshenq and Shishak:

A Case of Mistaken Identity” (Chronology and Catastrophism Review,

vol. VIII, pp. 36-46). Despite the superficial similarity of the names, the

fact is that Shoshenq I (as is generally agreed), never attacked Jerusalem

(which “Shishak” most certainly did).

Shoshenq does not relate that

he invaded Israel or that he conquered Jerusalem. He simply writes a list of

cities that he is presenting to the god Amun, and Jerusalem is not among them.

…. If Shoshenq had conquered Jerusalem and taken all the fabulous treasures out

of the temple there, he would certainly have made a big deal of it. Some have

pointed out that some of the inscription has been damaged and perhaps Jerusalem

was mentioned among the damaged section, but Jerusalem would have been the

prize and would have been mentioned at the beginning of the inscription, which

is still intact. ….

I summarised

some of Dr. John Bimson’s argument as follows in my university thesis:

A Revised History of the Era of King

Hezekiah of Judah

and its Background

‘King Shishak of

Egypt’

My Egypto-biblical

re-alignment will be fully in accordance with Velikovsky insofar at least as he

had removed one of the most fundamental pillars of the conventional Egyptian

chronology: namely, that Shoshenq I was ‘Shishak’. Whether Velikovsky was also

correct in his identifying of the biblical ‘King So of Egypt’ with one or other

Libyan Shoshenq … will still need to be determined.

Just How Important is

Shoshenq I in the Conventional Scheme?

Bimson has claimed that the

present identification of Shoshenq I with ‘Shishak’ is so firmly fixed in the

minds of the conventional historians that it constitutes a “major obstacle”

standing in the way of their acceptance of the revised scheme of ancient

history. …. Ever since Champollion proposed this identification, he says, it

has been well nigh universally accepted by the scholarly community, becoming

“axiomatic among Egyptologists and biblical scholars alike.

Superficially, the link

appears impressive enough. Apart from the fact that (i) Shoshenq I is

conventionally dated to the approximate time of ‘Shishak’, it seems (ii) his

name is similar to ‘Shishak’, and (iii) Shoshenq is known to have campaigned in

Palestine.

The reality, however, is very

much different from the appearance!

….

And I can add to this the

pertinent observation that historians - as a result of their dating Shoshenq I,

as ‘Shishak’, to the time of Rehoboam of Judah (c. 925 BC) - find themselves

having to look, for [biblical king of Egypt] ‘So’, at the time, say, of pharaoh

Tefnakht (c. 727-716 BC, conventional dates), a [Third Intermediate Period] ruler

of the 24th dynasty. But since it is immediately apparent that the name

‘Tefnakht’ is entirely inappropriate for ‘So’, proponents of this view must

then resort to such far-fetched explanations as this one mentioned by Grimal:

…. “Some scholars have treated [So] as a mistaken Hebrew spelling for the city

of Sais, in which case - by a process of metonymy - Hosea would have been

appealing to King Tefnakht [who reigned from there]”.

2 Kings 17:4, however, clearly

identifies ‘So’ as “King … of Egypt”; hence the name does not pertain to a

city, such as Saïs.

Kitchen moreover has listed a

number of reasons why he thinks that Tefnakht is unsuitable for ‘So’. ….

Gardiner has looked more

realistically to identify “So with the Sib’e, turtan of Egypt, whom

the annals of Sargon state to have set out from Rapihu (Raphia on the

Palestinian border) together with Hanno, the King of Gaza, in order to deliver

a decisive battle”. ….

Though such a view would need

to address why one whom the Second Book of Kings had entitled ‘King’, prior to

the fall of Samaria, had become, some half a dozen or so years later, a mere

Egyptian official (turtan); albeit an important one.

Name (Linguistic)

Arguments

The vocalisation of the

Egyptian hieroglyphs as Shoshenq is based upon the spelling of the

name Shushinqu (or Susinku) in Assyrian records from the C7th

BC. We find experts ranged on both sides in regard to whether the two names Shoshenq

and Shishak are sufficiently close to confirm their identity.

Gardiner, for instance, plainly felt that the Hebrew name was incompatible with

the hieroglyphic original. …. Kitchen … has on the other hand defended the

plausibility of the Hebrew rendering. More recently, Bimson … has accepted

Gardiner’s estimation that the name fit is not entirely compelling; whilst

Bimson’s critic, Shea … has fully supported Champollion’s identification.

….

The most problematical

linguistic aspect for the likes of Kitchen and Shea is the second vowel in the

name Shishak, about which Bimson has this to say: ….

... there is the omission of

the ‘n’ from the Hebrew name. Kitchen points to several instances of the ‘n’

being dropped from cartouches of the name Shoshenq during the 22nd Dynasty ....

Two of these involve the

prenomen Hedjkheperre, i.e. the prenomen borne by the Shoshenq normally

identified as the biblical Shishak; and two other instances are associated with

his known relatives. It is therefore possible that the Hebrew name Shishak

represents this abbreviated form of the Egyptian.

However, Kitchen’s case would

be stronger if there were instances of the ‘n’ being dropped in non-Egyptian

sources. The Assyrian Shushinqu preserves it, and it is retained in the Greek

form employed by Manetho and his excerptors…. Should we therefore expect the

Hebrew scribes to omit the ‘n’? Probably not.

With Velikovsky’s Shoshenq

(Sosenk) = ‘So’, any linguistic difficulty is greatly reduced, at least, since

the whole of ‘So’ is contained in the first syllable of the pharaonic name. And

we should not be surprised about the abbreviation of the name ‘Shoshenq’ to

‘So’, since, according to Kitchen: … “Abbreviations of private names are common

from the New Kingdom onwards”. More specifically, Kitchen tells here of

Shoshenq’s name having been actually shortened to ‘Shosh’ on scarabs.

Moreover, Hebrew shin (ש)

and samek (ס) are reasonably close in pronunciation. The difference

between the sh (ש) and s (ס) sounds could simply be one of

dialect as is apparent from the celebrated case in Judges 12:6 where the

Ephraïmites were distinguishable from the Gileadites in their inability to

pronounce the password, Shibboleth … which the Ephraïmites rendered as

Sibboleth ….

Shoshenq’s Activity in

Palestine

Whilst the linguistic argument

in favour of Champollion’s choice of Shoshenq as ‘Shishak’ has at least

something to recommend it, the same cannot be said I think for Shoshenq’s most

misunderstood actions in Palestine, as recorded on the Bubasite Portal at

Karnak. Shoshenq I’s activities in Palestine just cannot be made to fit the

bold campaign by ‘Shishak’ against Jerusalem!

By today’s standards

Champollion’s understanding of Shoshenq’s Bubasite list was, as Bimson has

noted, quite unsophisticated. Instead of his recognising all of the name-rings

on Shoshenq’s inscription as

being the names of towns and cities in Palestine, he believed that the list

included “the leaders of more than thirty vanquished nations”. ….

Among the names Champollion

read No. 29 as ‘Ioudahamelek’, which he took to be the name ‘Judah’ (Heb. יְהוּדָה)

followed by ‘the kingdom’474 – though, more preferably, it would be ‘the king’

preceded by definite article (Heb. : הַמֶּלֶךְ). Consequently,

Champollion translated this name-ring as “the kingdom of the Jews, or of Judah”

(cf. Hebrew ha(m)malcûth).

He thus concluded that Judah

was among the many “nations” that the pharaoh claimed to

have conquered.

Champollion’s reading of name

No. 29 was subsequently challenged by Brugsch, who made a new and detailed

study of the list. Brugsch identified names both before and after

No. 29 as belonging to Israel

as well as to Judah, and therefore felt that its position in the

list contradicted

Champollion’s reading.475 The now generally accepted view, according to Bimson,

is that proposed by Müller:476 namely, that No. 29 stands for a place, Yadha(m)melek.

Whilst this location has not yet been identified, its position in the list

would definitely seem to suggest that it refers to a location in the NW coastal

plain of Israel, far from Jerusalem. This fact, however, does not appear to

have weakened acceptance of the identification of Shoshenq with ‘Shishak’.

….

A considerable number of names

in the Bubasite list had come to be identified with towns in Israel and Judah,

establishing that Shoshenq’s forces had campaigned in Palestine. Unlike in the

campaign of ‘Shishak’, however, the kingdom of Israel too was attacked according

to Donner. ….

In regard to certain

‘explanations’ that “Rehoboam might have captured various towns in Israel, or

that the pharaoh was simply prepared to override friendship with Jeroboam for

the sake of political gain, these”, says Bimson, “are either flatly contrary to

Scripture (1 Kings 12:21-4), or completely unattested therein”. …“Such

conjectures are necessary”, he adds, “only because of the identification of

Shoshenq I with Shishak. It is entirely consistent with the Bible’s portrayal

of Shishak as Jeroboam’s ally that it contain no reference whatsoever to an

Egyptian invasion of Israel”.

Jerusalem Not Listed by

Shoshenq

Scholars for and against

Champollion’s reconstruction, alike, have generally concluded that Jerusalem is

not even mentioned in Shoshenq’s Bubasite list. Velikovsky, for instance,

claimed that: … “Neither Jerusalem, Hebron, Beer-Sheba, Bethlehem, nor any

other known place was among the names on the list; nor was Jaffa, Gath, or Askelon”.

And Bimson has regarded

“Shoshenq’s failure to include Jerusalem in his list of cities ...” as being

far more serious than any other problem raised by the opponents of the

conventional view; “a major stumbling block”. ….

But even the proponents of the

Shoshenq = ‘Shishak’ view are puzzled by this apparent omission. Judah’s

wealthy capital features in the Scriptures as being the prime target of the

biblical pharaoh’s expedition; but when we turn to Shoshenq’s inscription, as

Hermann says: …. “It is remarkable that Jerusalem does not seem to be mentioned

on it, and does not therefore belong among the places seized ...”.

Kitchen also thinks it

extremely unlikely that Jerusalem ever featured in any of the sections of the

bas-relief now damaged. ….

Shea, on the other hand,

claims to have found Jerusalem and its environs described in various of

Shoshenq’s name rings. ….

David Rohl,

admittedly, does make a very good fist of trying to match Ramses II with

Shishak. But, as we shall read in the following critique, this ‘new’ version of

Shishak runs into some insurmountable problems, thus placing “the New

Chronology … under considerable threat”. Rohl, like James (Centuries of

Darkness, 1990), still manages to score telling points against convention,

but his mid-way revision leaves him wandering in something of a no

man’s land. Dale Murphie (recently deceased) has provided the following rather

devastating “Critique of David Rohl’s A Test of Time” (C and C Review, 1997:1,

p. 31):

According to David Rohl, ‘The

evidence from the Egyptian monumental reliefs, artefacts and documents points

to the identification of Ramesses II as the historical counterpart of the

biblical Shishak, conqueror of Jerusalem’ [Test of Time, I, p. 170:

‘Conclusion 8’]. The evidence certainly points to Ramesses II having been in

the Judaean capital but is this conclusion the only option? ….

Having sketched Ramesses II

into the Shishak position, Rohl takes on the conventional view that Shoshenq of

Dynasty XX [sic] was the biblical Shishak. His argument is cogent, convincing

and compelling. Even Kenneth Kitchen, reigning champion of the Third

Intermediate Period (TIP) dogma, must surely come under pressure to yield

ground, opening the way to a dramatic TIP revision. The great advance here is that

David demonstrates Shoshenq is not Shishak - and the book is worth its price

for this gem alone - but he does not actually prove Ramesses II is

Shishak. He merely establishes that this would be the case if his

input data are comprehensive and accurate. I suggest they are neither.

In Rohl’s historical scheme,

this is a paramount issue. He gives three full chapters (4-6), plus his Preface

as reinforcement, to the proposition that Ramesses II is Shishak. If he is

mistaken here, the New Chronology comes under considerable threat. It is worth

examining the general milieu into which Rohl thrusts Ramesses II, to see how

snugly he fits. There seem to be a number of problems, stemming from biblical

evidence that the regional power of Egypt became diminished and the Judaean

state re-established full independence in this very period.

Firstly, given Ramesses’ 67

year reign, he would only have reached Year 22 when Asa of Judah, grandson of

Rehoboam, ascended his throne. The significance of this date is that only one year

previously Ramesses concluded his famous treaty with the Hittite King,

Hattusilis. At this stage, with Egypt and the Hatti entering a long period of

unprecedented harmony, consider the remarkably provocative actions of miniscule

Judah. This tiny nation, under her new king, flouted the Egyptian/Hatti pact

(which provided for mutual aid in just such an event), by starting the greatest

fortress building phase of its entire history and developing a standing army of

540,000 men [II Chronicles 14:6-8] – and where did this military build up take

place? Not in some distant corner of Egyptian/Hatti territory, away from prying

eyes, but right in the demilitarised zone between the two powers, where all

might see and not be under the slightest doubt that Judah meant business.

And that is not

the end of the problem for Rohl.

Murphie

continues:

To compound this difficulty,

the Hebrew annals declare that in Asa’s 10th Year [II Chronicles

14:9-15] (Ramesses’ 31st year in the New Chronology) Judah was

invaded from the south. However the biblical record says the foe was neither

Ramesses nor Hattusilis (as would be expected in Rohl’s scenario) but another

character entirely: Zerah the Ethiopian. Would Hatti and Egypt stand back to

allow this fourth party with a massive army (suggested as from Arabia rather

than Nubia) to invade their territory? Moreover, Zerah’s expedition

suffered a major thumping at the hands of the Judaean upstart, enhancing Asa’s

reputation throughout the region. Still the New Chronology has us believe that

Ramesses and Hattusilis did nothing! Even if Zerah was acting in some way as agent

provocateur of one of the major players (logically Egypt) in an attempt to

take out the Judaean Maginot Line of fortresses, how could Ramesses

have tolerated Asa’s humiliation of his agent?

If Ramesses II was Shishak,

there never was a time when, nor a place where, such a result for Asa could

have been more inappropriate or unlikely. ….

Briefly here,

also, Murphie touches on the inadequacies of Rohl’s chronology in relation to

the Queen of Sheba:

At the beginning of this time

frame Shishak is tied chronologically to another celebrity who, like Zerah,

simply cannot be ignored. On p. 178 Rohl mentions the Egyptian princess, bride

of Solomon, but pays little attention to the contemporary visit of the Queen of

Sheba, to whom he assigns 2 lines on p. 32 and a patronising comment about

Velikovsky on p. 402. By aligning Dynasty XIX with the middle to near end of

the United Monarchy of Israel, the New Chronology lacks a suitable candidate

for Solomon’s celebrated visitor. It is not good enough to stay with the

received opinion that she was a denizen of the south-west regions of Arabia

Felix, when Josephus [Antiquities of the Jews, VIII, vi, 5] informed

us that she was the Queen of Egypt and Ethiopia …. Further, the Ethiopian Kebra

Nagast (The Book of the Glory of the Kings), discussing their Queen’s

visit to Solomon, delivers her name as Makeda, almost identical to the

royal name of Dynasty XVIII Queen Hatshepsut Makera, used repeatedly

in the Dier [sic] el-Bahri mortuary complex inscriptions of her trading mission

to Punt, placing the events in Dynasty XVIII.

Kings Rehoboam and Jeroboam I

“Also,

Jeroboam son of Nebat rebelled against the king. He was one of Solomon’s officials,

an Ephraimite from Zeredah, and his mother was a widow named Zeruah”.

I

Kings 11:26

Jeroboam

and “Shishak”

Jeroboam [I] is

not - unlike King Solomon’s other adversaries, Hadad the Edomite and Rezon son

of Eliada - actually referred to as a satan … but as ‘lifting up his

hand against the king’ ….

Thus we read

(vv. 27-39):

Here is the account of how

[Jeroboam] rebelled against the king: Solomon had built the terraces and had

filled in the gap in the wall of the city of David his father. Now Jeroboam was

a man of standing, and when Solomon saw how well the young man did his work, he

put him in charge of the whole labor force of the tribes of Joseph.

About that time Jeroboam was

going out of Jerusalem, and Ahijah the prophet of Shiloh met him on the way,

wearing a new cloak. The two of them were alone out in the country, and Ahijah

took hold of the new cloak he was wearing and tore it into twelve pieces. Then

he said to Jeroboam, ‘Take ten pieces for yourself, for this is what the Lord,

the God of Israel, says: ‘See, I am going to tear the kingdom out of Solomon’s

hand and give you ten tribes. But for the sake of my servant David and the city

of Jerusalem, which I have chosen out of all the tribes of Israel, he will have

one tribe. I will do this because they have forsaken me and worshiped Ashtoreth

the goddess of the Sidonians, Chemosh the god of the Moabites, and Molek the

god of the Ammonites, and have not walked in obedience to me, nor done what is

right in my eyes, nor kept my decrees and laws as David, Solomon’s father, did.

But I will not take the whole

kingdom out of Solomon’s hand; I have made him ruler all the days of his life

for the sake of David my servant, whom I chose and who obeyed my commands and

decrees. I will take the kingdom from his son’s hands and give you ten tribes.

I will give one tribe to his son so that David my servant may always have a

lamp before me in Jerusalem, the city where I chose to put my Name. However, as

for you, I will take you, and you will rule over all that your heart desires;

you will be king over Israel. If you do whatever I command you and walk in

obedience to me and do what is right in my eyes by obeying my decrees and

commands, as David my servant did, I will be with you. I will build you a

dynasty as enduring as the one I built for David and will give Israel to you. I

will humble David’s descendants because of this, but not forever’.’

Jeroboam was

obviously a man of great talent, making an impression, first on King Solomon,

and, then, on Pharaoh Shishak.

Solomon,

realising that the great man had become a danger (v. 40), “tried to kill

Jeroboam, but Jeroboam fled to Egypt, to Shishak the king, and stayed there

until Solomon’s death”.

Pharaoh Shishak

can only be, according to my estimations, the very long-reigning (54 years) Thutmose III

of the Eighteenth Dynasty.

I (and others) have

calculated that Thutmose I was the biblical “Pharaoh” during King

Solomon’s early reign, who had given his “daughter” to King Solomon in an

“alliance”. He reigned into approximately the first decade of King Solomon’s

reign.

For more on

this, see e.g. my article:

Thutmose I was

succeeded by Thutmose

II of uncertain length of reign – but perhaps similar to his

predecessor, about 13 years.

The “Queen of

Sheba”, who had visited and married Solomon, then left to marry Thutmose II.

She was Queen Hatshepsut.

These were

political marriages, for the purpose of linking powerful kingdoms such as

Israel and Egypt.

When Thutmose II

died, Thutmose

III came to the throne, for approximately the last two decades

of Solomon’s reign.

“According to

custom”, Queen Hatshepsut “began acting as Thutmose III’s regent, handling

affairs of state until her stepson came of age. …. After less than seven years,

however, Hatshepsut took the unprecedented step of assuming the title and full

powers of a pharaoh herself, becoming co-ruler of Egypt with Thutmose III”.

Although King

Solomon had been, as Senenmut (Senmut) a mighty force in Egypt, in close

association with Hatshepsut, his influence there, at the time when Jeroboam

fled to Shishak, must have been well on the wane, with a maturing Thutmose III

now in the ascendancy.

In my article:

Solomon

and Sheba

I had written on this:

Thutmose III in the

Ascendant

Thutmose, far from having

engaged in damnatio memoriae, actually placed a statue of Senenmut in

his Karnak temple and was ‘willing to see honor done to him, at least

posthumously’ …. Thutmose III's apparent respect for his mentor might explain

why such a military-minded Pharaoh left it 5 years after Solomon's death before

invading Jerusalem and sacking the Temple … (as the biblical ‘Shishak’).

However cracks in their

relationship surfaced near the end of Solomon's life when Jeroboam, chosen by

God ‘to tear the kingdom from the hand of Solomon’, feared for his life and

fled to ‘Shishak’ in Egypt, where he remained until Solomon's death (I Kings

11:26, 31, 40). Perhaps during the last few years of Hatshepsut's reign, with

Solomon in decline, Thutmose Ill began to assert his independence. He may have

realised that it would fall to him to rectify Egypt's economic problems. He

accomplished this after Hatshepsut's death, by embarking upon a series of mighty

military conquests.

Senenmut's Decline and

Death

‘Senenmut's continuing

goodwill at court seems to have continued unabated during most … of

Hatshepsut's floruit’ …. Hatshepsut died in about Regnal Year 21. …. There have

been all sorts of intriguing guesses about Senenmut's demise. Schulman … who

estimated Senenmut's age at over 50 in Regnal Year 16, thinks ‘it would not at

all have been surprising for [Senenmut] to have died from natural causes at a

relatively old age, without our having to suppose a fall from the royal favour

which resulted in his death’.

Evidence for

Solomon’s weakening would be that, whereas, before, he had been able to slay

his adversaries (e.g., Adonijah, Joab, Shimei), he was not able to do away with

Jeroboam, who would, after Solomon’s death, go on to rule strongly “for

twenty-two years” (I Kings 14:20).

That Jeroboam

was prized by Shishak - as Hadad the Edomite earlier had been, by “Pharaoh” -

is apparent from the fact that Shishak gave him an Egyptian princess for a

wife, Ano, according to the LXX (I Kings 12:24):

And Jeroboam heard in Mizraim {gr.Egypt}

that Solomon was dead; and he spoke in the ears of Shishak {gr.Susakim}

king of Mizraim {gr.Egypt}, saying, Let me go, and I will depart into

my land; and Shishak {gr.Susakim} said to him, Ask any request, and I

will grant it thee. And Shishak {gr.Susakim} gave to Jeroboam Ano the

eldest sister of Thekemina his wife, to be his wife: she was great among the

daughters of the king, and she bore to Jeroboam Abia his son: and Jeroboam said

to Shishak {gr.Susakim}, Let me indeed go, and I will depart. And

Jeroboam departed out of Mizraim {gr.Egypt}, and came into the land of

Sarira that was in mount Ephraim, and thither the whole tribe of Ephraim

assembles, and Jeroboam built a fortress there.

The Hebrew text

lacks any mention of an Egyptian wife given to Jeroboam (I Kings 12:1-2):

“Rehoboam [son of Solomon] went to Shechem, for all Israel had gone there to

make him king. When Jeroboam son of Nebat heard this (he was still in Egypt,

where he had fled from King Solomon), he returned from Egypt”.

As I have said

before, the revision, when properly aligned, can be fruitful, whereas the

conventional system is sterile. Regarding Jeroboam’s Egyptian wife, Dr. I.

Velikovsky thought to have found historical evidence for her (Ages in

Chaos, ch. iv: “Princess Ano”, pp. 180-181):

In the Metropolitan Museum of

Art in New York there is preserved a canopic jar bearing the name of Princess

Ano [his ref. No. 10.130.1003]. The time when the jar originated has been

established on stylistic grounds as that of Thutmose III. No other references

to a princess of such name is found in any Egyptian source or document.

Of course this

data suited perfectly Dr. Velikovsky’s revision, according to which Shishak

(Susakim) was Thutmose III (p. 181): “The existence of a princess by the name

of Ano in the days of Thutmose III lends credence to the information contained

in the Septuagint and gives additional support to the identification of Shishak

or Susakim of the Septuagint with the pharaoh we know by the name Thutmose

III”.

Jeroboam

and the cow-goddess Hathor

Jeroboam I will

ultimately be disgraced and will fall from grace. I Kings 14:9-11 tells of it:

‘You have done more evil than

all who lived before you. You have made for yourself other gods, idols made of

metal; you have aroused my anger and turned your back on me.

Because of this, I am going to

bring disaster on the house of Jeroboam. I will cut off from Jeroboam every

last male in Israel—slave or free. I will burn up the house of Jeroboam as one

burns dung, until it is all gone. Dogs will eat those belonging to Jeroboam who

die in the city, and the birds will feed on those who die in the country. The

Lord has spoken!’

That fearful

prophecy, uttered by Ahijah, would be fulfilled in the next reign.

In a marvellous

article, “Aaron, Jeroboam, and the Golden Calves” (JBL, Vol. 86, No.

2, Jun., 1967, pp. 129-140), authors Moses Aberbach and Leivy Smolar will list

“thirteen points of identity” between the accounts of Aaron and the Golden Calf

(Exodus 32) and Jeroboam and his Golden Calves (I Kings 12:38 f.).

Might we take it

even further, that Jeroboam’s “golden calves” were, like Aaron’s creature,

vestiges from former contact with Egypt?

Dr. Eva Danelius

has, indeed, established a firm Egyptian religious connection for Jeroboam I in

“The Sins of Jeroboam Ben-Nabat” (The Jewish Quarterly Review, vol.

LVIII, no. 3, 1968):

“…. Faced with the fact, that

Jeroboam's "calves" were representations of a cow-goddess-the next

question is that for the prototype to them, or her.

Naturally, attention is first

focussed on Egypt-the country which had extended such ample hospitality to the

exiled Jeroboam, where he had married, and where his son had been born. The

search is not in vain : a cow like the heifers described by Josephus : a

reddish young animal, made, not molten, covered with gold, in a small shrine of

her own, a cow inscribed with the name of a Pharao-who was considered a -has

indeed been found: it is the famous Hathor cow from the Hathor shrine in the

temple at Deir el-deity43Bahari.

The magnificent temple at Deir

EI-Bahari was erected in a bay of the cliffs on the west side of the Nile at

Thebes, by the great queen Hatshepsut of the famous XVIIIth dynasty. In the

winter, 1906, Mr. Naville, during his excavations of the XIth dynasty temple

which preceded that of Hatshepsut, discovered the shrine of Hathor. The shrine

was built by Thutmoses III, Hatshepsut's husband, and successor to the throne.

Within it stood a great life-size image of the cow-goddess. "Never before

had a cult-image of this … size and beauty been found intact within its

shrine".

“. . . Hathor is a goddess who

comes out of a mountain-therefore a cave was cut in the rock. . . The shrine is

a cave about 10 ft long and 8 ft high" (it is 5 ft across) it is hewn in a

rock. . . it has been lined allround with slabs of sandstone . . . the roof is

a vault consisting of two stones abutting against each other and cut 45in the

form of an arch. There never was any pavement; the cow stood on the rough

rock".

"The cow is of sandstone.

She is of natural size and in her shape a perfect likeness of the cows of the

present day. Her colour is a reddish brown, with spots which look like a

four-leaved clover. . . in some texts, these spots are replaced by stars . . .

It seems that there are animals with this particular colour and spots. Probably

this was the sign that they were the incarnation of the goddess, just as some

particular … marks distinguished the Apis Bull . . .

"Hathor is the goddess of

the mountain. She comes out of her cave and goes towards the river to the

marshes . . . In the Book of the Dead, immediately at the foot of the mountain

out of which she comes, we … see quite a forest of high papyrus plants . .

."

"The head, neck, and

horns of this cow were certainly originally covered with gold: faint traces of

it may be seen in the nostrils and on the horns; but the gold must have been

very thin, like the very delicate coating which covers some statuettes, and

which is metal beaten so thin that the sculpture is made with the same care as

if the coating did not exist. It is the case with the cow. . ."

"According to the

judgement of experts, this cow is perhaps one of the finest representations of

an animal … that antiquity has left us.

On the neck of the cow is the

cartouche of Amenhotep II, son and successor of Thutmoses III.

The XVIIIth dynasty were

fervent worshippers of Hathor, and so were many of its successors. The

sculpture of Deir EI-Bahari was certainly not the only one of its kind, some of

which must have been seen by Jeroboam. We know, too, that from the days of the

Old Kingdom Egyptian princesses from the harim of the Pharao had been

priestesses to Hathor and especially devoted to this goddess-and Jeroboam's

wife Ano might have been one of them. The possibility must be considered, therefore,

that Jeroboam during his stay in Egypt accepted the worship of Hathor, the

heavenly cow, the Great Lady, Mistress of Heaven and Earth. He seems to have

decided already then and there, to introduce her service in his native land,

should the prophecy of Ahija the Shilonite ever come true”.

The

Greeks

The contemporary

tomb of Rekhmire, like that of Senenmut, features Aegean emissaries, whose

specific ethnicity and lands of origin are debated.

… Introduction of

a new term--The terms Keftlu and "Islands

“In the midst of

the Great Green" are found In conjunction in

the tomb of the Vizier Rekhmire during the reign

of Thutmose Ill. Historically, one may infer that the new

term, "Islands in the midst of the Great Green" was

designed to describe the Mycenaeans, who first came in touch with

Egypt during the time of Thutmose III”.

A massive

problem, of course, is the conventional archaeology with its Dark Ages for

Greece. Previously I had noted:

Thanks to historical revisions

… we now know that the ‘Dark Age’ between the Mycenaean (or Heroic) period of

Greek history (concurrent with the time of Hatshepsut) and the Archaic period

(that commences with Solon), is an artificial construct. This makes it even

more plausible that Hatshepsut and Solomon were contemporaries of ‘Solon’. The

tales of Solon's travels to Egypt, Sidon and Lydia (land of the Hittites) may

well reflect to some degree Solomon's desire to appease his foreign women -

Egyptian, Sidonian and Hittite - by building shrines for them (I Kings 11: 1,

7-8).

John R. Salverda, in a

letter to me, suggested that the Greeks may have derived “Europa” from the

name, Jeroboam:

…. Exiles from Jeroboam’s

kingdom founded colonies in Mycenaean lands, including Greece (where the

“virgin Israel” was likely even known by a feminine corruption of Jeroboam’s

name “Europa”); Where a famous set of twins fought in the womb, and one of the

twins (Acrisius) set up a twelve tribe “Amphictyon” to maintain a special

temple. This Greek temple was located at a place known as “Pytho” (a likely

transliteration of the term “Bethel,” also called Delphi) thought to be named

for “Python” (a possible corruption of “Beth-Aven” or without the slur

“Beth-On”), where Apollo (Identified by the Greeks with the Egyptian Horus)

slew the great serpent (as Horus did Seth/Apophis). As the Bethel shrine was

turned into a copy of the Jerusalem Temple, so the Pyhtian temple of Apollo

shares many detailed coincidences with the Judean Temple. The “omphalos” as the

“Eben Shetiyah” (the respective “center stones” of the Earth), the Adyton as

the Holy of Holies (the sanctuary of forbidden entry), the goat sacrifice

(complete with special treatment for the entrails), the fumigation (sweet

smelling incense), and ritual bathing (in specifically “living water”) … there

are many other corresponding ritualistic and anecdotal features shared by these

two temple schemes too numerous to outline in this forum! Well, before going on

too long, notice all of the “Egyptian” motifs in this narrative. ….

What is certain

is that Solomonic archaeology emerges in abundance when all of the seemingly

disparate elements of ancient history are brought together, as indeed now they

must be.

These, we have

found, are:

The supposed C18th BC world of Iarim-Lim

(now King Hiram), and the archaeology of Alalakh (tying in with the

Philistines);

The contemporaneous Shamsi-Adad

I (now Hadadezer) - son of Uru-kabkabu (Rekhob) - and his ‘sons’, with

Iasmakh-Adad as a potential Hadad the Edomite;

The Era of Hammurabi and

Zimri-Lim (Rezon), son of Iahdulim (Eliada). The Solomonic-like architecture at

Mari.

The supposed C15th BC (actually

only about a generation later than the above) world of Idrimi

(Hadoram) at Alalakh, rightly situated as a contemporary of Hatshepsut and

Thutmose III of Eighteenth Dynasty Egypt.

Senenmut (Solomon) in

Hatshepsut’s Eighteenth Dynasty Egypt. Late Bronze I-II Age approximately.

Not Iron II where the current

archaeologists mistakenly look for King Solomon.

This is the age of those Minoan

and Aegean Greeks depicted in the reliefs of Senenmut and Rekhmire.

The so-called (c. 600 BC) age

of Solon of Athens (Solomon), whose laws are actually Jewish - some being even

as late as those of Nehemiah. See e.g. E. M. Yamauchi’s, “Two Reformers

Compared: Solon of Athens and Nehemiah of Jerusalem" (Bible

world, New York: KTAV, 1980. pp. 269-292).

Rehoboam

not so “young”

I Kings 14:25-26:

In the fifth year of King

Rehoboam, Shishak king of Egypt attacked Jerusalem. He carried off the

treasures of the Temple of the Lord and the treasures of the royal palace. He

took everything, including all the gold shields Solomon had made.

and

correspondingly we read from:

2 Chronicles 12:2-4, 9:

Shishak king of Egypt attacked

Jerusalem in the fifth year of King Rehoboam. With twelve hundred chariots and

sixty thousand horsemen and the innumerable troops of Libyans, Sukkites and

Cushites that came with him from Egypt, he captured the fortified cities of

Judah and came as far as Jerusalem. …. When Shishak king of Egypt attacked

Jerusalem, he carried off the treasures of the Temple of the Lord and the treasures

of the royal palace. He took everything, including the gold shields Solomon had

made.

Fatefully, and

wrongly - as we have found - the conventional history has (following

Champollion) synchronised this most significant biblical event with the main Palestinian

campaign of pharaoh Shoshenk (Shoshenq) I of Egypt’s 22nd (so-called

Libyan) dynasty.

We have, though

(in this case following Velikovsky), constructed a totally different scenario.

In our revision,

Senenmut’s (who was King Solomon) floruit in Egypt would correspond

approximately to the mid-to-late phase of Solomon's reign = Years 1-16/19 of

Thutmose III.

Hatshepsut's

reign is dated by the regnal years of Thutmose III.

Prior to this

period, King Solomon had completed his great building projects in Jerusalem,

and, towards its end, he fell away from pure Yahwism into a decadent phase,

building shrines to pagan gods for his foreign wives (I Kings 1:18). In perfect

accord this, N. Grimal says that Senenmut “was a ubiquitous figure throughout

the first three-quarters of Hatshepsut's reign. He oversaw some of the most

famous temples and shrines built during the co-reign of Hatshepsut and Thutmose

III, and [princess] Neferure’s name also figures in some of these. …”.

King Rehoboam’s

immaturity early during his reign would make one think that he was only young.

Indeed, his son Abijah will refer to Rehoboam as if he had been (2 Chronicles

13:7): ‘Some worthless scoundrels gathered around him and opposed Rehoboam son

of Solomon when he was young and indecisive and not strong enough to

resist them’.

The Hebrew word na‘ar

(נַ֙עַר֙), translated here as “young” needs to take into

account the fact that (I Kings 14:21): “Rehoboam son of Solomon … was forty-one

years old when he became king …”. The common word, na‘ar,

also used by a reluctant prophet Jeremiah (Jeremiah 1:6): ‘“Alas, Sovereign

Lord’, I said, ‘I do not know how to speak; I am too young”, must also

include the sense of disposition, of temperament.

However, King

Rehoboam, who had formerly told the people: 10-11): ‘… My little finger shall

be thicker than my father’s loins. … whereas my father burdened you with a

heavy yoke, I will add to your yoke: my father hath chastised you with whips,

but I will chastise you with scorpions’, was wise enough to humble himself

during the invasion of Shishak king of Egypt (2 Chronicles 1:6): “The leaders

of Israel and the king humbled themselves and said, ‘The Lord is just’.”

Dr. Eva Danelius

looked to recreate the scene at the time in a revised context (“Did Thutmose

III Despoil the Temple in Jerusalem?”):

The Empire of the Hebrews,

which David had taken such great pains to build, fell to pieces immediately

after the death of his son King Solomon. Hadad seems to have returned and

conquered Edom even before King Solomon's death - or, at all events,

immediately thereafter (I Kings 11:22). Jeroboam was sent for and called back

to his native Ephraim by the elders of the ten Northern tribes to be made

"King over all Israel". Rehoboam, Solomon's son and successor, was

left with his native tribe of Judah alone (I Kings 1:13; 12:20).

Rehoboam had lost an empire.

Now he did everything possible to ensure the safety of the tiny kingdom with

which he was left. Anticipating an invasion, Rehoboam put his country into a

state of defence (II Chron. 11:5-12): he closed off all the roads and defiles

leading up into "the high rocky fortress of Judaea" (23) with a semi-circle

of fifteen fortresses, he "put captains in them, and store of victual, and

of oil and wine . . . shields and spears, and made them exceeding strong",

to withstand a prolonged siege.

Rehoboam was well advised to

do so, being surrounded by enemies of the House of David: in the south Edom, in

the west the lands of the five Philistine kings, and in the north the

Israelites, who had just successfully rebelled against him. The only road which

he kept open was that which led via Jericho and the fords of the Jordan to the

Ammonites, to whom he was related through his mother (I Kings 14:21), and from

whom he could hope for help against a foreign invader.

Curiously enough, the Bible

does not mention any fortress which would protect Judah's northern border against

Israel. This gap is filled by Josephus, who reports that Rehoboam, after

completing the strongholds in the territory of Judah, constructed walled cities

in the territory of Benjamin, which bordered Judah to the north ….

While the king of Judah prepared

for defence, the Pharaoh prepared for an attack.

The Egyptian pharaoh who

conquered Jerusalem during Rehoboam's reign has been identified with Sheshonk

I, who had a list of Palestinian cities inscribed on the Temple walls at

Karnak. The list is most fragmentary, and it is doubtful whether it refers to a

campaign at all. Most of the discernible names refer to localities in northern

Palestine, which, in Shishak's time, belonged to the Kingdom of Israel. The

name "Jerusalem" does not appear at all. Some scholars maintain,

therefore, that the main attack was not launched against Judah, but against

Israel, which suffered serious destruction …. This contention, however, can

only be upheld by scholars who are willing to sacrifice the reliability of the

Bible (and of Josephus) - which this writer refuses to do ….

The Masoretic Text which has

come down to us was written by Judaeans hundreds of years after the Kingdom of

Israel had ceased to exist. The Judaeans hated this kingdom and its first king,

Jeroboam the heretic. The redactors of the text would have been only too glad

to report that Jeroboam was punished for his heresy, that it was his

land that was conquered, his capital which was plundered, and the

temple at Beth-El that was despoiled. - There is not a word of this, but

definite proof to the contrary.

While Rehoboam was feverishly

preparing his country for war, Jeroboam indulged in entirely peaceful

activities. He built a royal palace at Shechem in the hope of making it his

capital. He built a second one at Pnuel …. And he embarked on a religious

revolution which weakened the military capacity of his country considerably ….

During all those years, Jeroboam was certainly as well aware of the military

preparations going on in Egypt as was his southern neighbour the king of Judah.

It seems that Jeroboam judged the situation correctly, as far as his kingdom

was concerned: no unfriendly act of the Pharaoh against Israel is as much as

hinted at by the Chronicler, who reports:-

And it came to pass, when

Rehoboam had established the kingdom, and had strengthened himself, he forsook

the law of the Lord, and all Israel with him. And it came to pass, that in the

fifth year of king Rehoboam Shishak king of Egypt came up against Jerusalem,

because they had transgressed against the Lord ... And he took the fenced

cities which pertained to Judah, and came to Jerusalem ... So Shishak king of

Egypt came up against Jerusalem, and took away the treasures of the house of

the Lord, and the treasures of the king's house; he took all ... (II Chron.

12:1-2, 4, 9)

An even more detailed account

has been preserved by Josephus, who closes with the words: "This done, he

[i.e. the Pharaoh] returned to his own country." Neither source mentioned

any hostility against Israel.

Velikovsky had

put out this challenge to conventional scholars regarding the forts of Judah:

The walled cities fortified by

Rehoboam (II Chronicles 11:5ff.) may be found in the Egyptian list. It appears

that Etam is Itmm; Beth-zur – Bt Sir; Socoh – Sk. Here is a new field for

scholarly inquiry: the examination of the list of the Palestinian cities of

Thutmose III, comparing their names with the names of the cities in the kingdom

of Judah. The work will be fruitful.

This was coupled

with his pointed remark that, among the 119 cities listed by Thutmose III,

there were many cities “which the scholars did not dare to recognize: they were

built when Israel was already settled in Canaan”.

Unfortunately for this part of Velikovsky’s thesis, P.

Clarke (in “Was Jerusalem the Kadesh of

Thutmose III’s 1st Asiatic campaign?—topographic and petrographic evidence”, p.

49) has well shown that Velikovsky had completely mis-identified these

supposed forts of Judah.

What

sort of a name is “Shishak”?

Dr.

Velikovsky himself did not actually attempt to connect “Shishak” to any of the

Egyptian names of pharaoh Thutmose III, but merely alluded to Josephus‘s

information that the Egyptian conqueror’s name was “Isakos”, or “Susakos”, and

also to the Jewish tradition that the name “Shishak” was from Shuk,

“desire”, because the pharaoh had wanted to attack Solomon, but had feared him.

A right

chronology

Criticisms of Dr. I.

Velikovsky’s choice (in Ages in Chaos, I, 1952) of pharaoh

Thutmose III for the biblical “Shishak king of Egypt” tend to focus on four

crucial areas: (i) chronology (naturally, since

Velikovsky has Thutmose III about 500 years later than does the conventional

estimate); (ii) the name; (iii) the relevant campaign against Jerusalem;

and

(iv) the booty.

Conventionally, Shoshenk I

of the 22nd (so-called “Libyan”) dynasty is considered to be the right

candidate, given that he has been dated to the time of kings Solomon and

Rehoboam; his name is phonetically like “Shishak”; and he is known to have

campaigned in Judah.

Though it is now widely

thought that pharaoh Shoshenk I did not at any stage attack Jerusalem (as

“Shishak” most certainly did).

Inevitably,

Velikovsky’s vital (for posterity) Eighteenth Dynasty reconstruction, snugly

aligned against the United (and later Divided) Monarchy of Israel, must lead

him to the conclusion that the long-reigning (54 years) pharaoh Thutmose III

was the same ruler as the biblical Shishak. Demonstrating this to be the case

in all its major details, though, has turned out to be more elusive, not only

for Velikovsky, but for those who have followed him here.

I, for my part,

am convinced that Velikovsky was entirely correct in this identification of his

(though not in his reconstruction of the whole biblico-historical scenario) and

I have added a possible extra dimension to the revision by introducing Senenmut

(Senmut) as King Solomon.

As previously

noted, Senenmut’s floruit in Egypt would correspond to the mid-to-late

phase of Solomon’s reign. In perfect accord with this, N. Grimal says that

Senenmut “was a ubiquitous figure throughout the first three-quarters of

Hatshepsut's reign”.

Name

“Shishak” for revisionists

Reconciling the

name, “Shishak”, with the mighty Eighteenth dynasty pharaoh, Thutmose III, was

one of Dr. Immanuel Velikovsky’s pressing tasks towards establishing this

proposed biblico-historical synchronism as a sturdy pillar of his historical

revision. Other major challenges relating to this were to connect the geography

of Thutmose III’s First Campaign to the brief biblical accounts about

“Shishak king of Egypt”; and to demonstrate that the inscribed Karnak

treasures from this campaign could be matched to those of the Solomonic

reign (his palace and the Temple of Yahweh).

Admittedly the

name Shoshenk (var. Shosenq, Soshenq) is, phonetically speaking - and

despite Dr. Bimson’s useful criticisms of it in his “Shoshenq and Shishak” - a

far more obvious fit for “Shishak” (Heb. Šiwšaq: שִׁישַׁק)

than is the name “Thutmose” (and perhaps than any other pharaonic nomen).

The various

names known for pharaoh Thutmose III are provided here by Phouka:

Horus Name

|

Kanakkht Khaemwaset

|

Nebty Name

|

Wahnesyt

|

Golden Horus Name

|

Djeserkhau Sekhenpehti

|

Praenomen

|

Menkheperre "Lasting are the Manifestations

of Re"

|

Nomen

|

Thutmose" Born of the god Thoth"

|

|

|

Manetho

|

Misphragmuthosis, Mepharamuthosis

|

King Lists

|

|

Alternate Names

|

Totmes, Thutmos, Thumoses, Tuthmoses

|

It needs to be

kept well in mind, however, that “Shishak” was the name by which this

person was known to the Jews; so it may not necessarily even have been an

Egyptian name.

A

similar name, “Shisha” (Heb. Šiyša‘:שִׁישָׁא) - practically identical to

“Shishak” but lacking the final k sound (Heb. qôph) - does

occur in the First Book of Kings as the father of two of King Solomon‘s

highest court officials, scribes (4:3).

It is generally

thought that “Shisha” is an Egyptian name, as with one of this man’s sons,

Eli-horeph.

Curiously,

Shisha’s name is variously rendered in the Old Testament as “Seraiah” (2 Samuel

8:17); as “Sheva” (20:25); and as “Shavsha” (I Chronicles 18:16), which

variability might perhaps indicate its foreignness.

Another very

close fit for the name “Shishak” is the biblical name “Shashak” (Heb. Šašaq) of

I Chronicles 8:14, 25.

{ŠŠK is actually

an atbash cryptogram in Jeremiah 25:26; 51:41}.

If, on the other

hand, the name “Shishak” is to be sought amongst those pharaonic

titles of Thutmose III, then one might consider K. Birch‘s suggestion that it

could derive from Thutmose III’s Golden Horus name, Djeser-khau (dsr h‘w)

[“Chase a Cow”, as some have rendered it]. Birch has written: “... the (Golden)

Horus names of Thutmose III comprise variations on: Tcheser-khau, Djeser-khau …

(Sheser-khau?) …”. (“Shishak Mystery?”, C and C Workshop, SIS, No. 2,

1987, p. 35).

This Golden

Horus name means “holy-of-diadems”.

Whilst Birch’s

ingenious explanation, and the others, may all have merit, my own particular

preference, at this point of time at least, is that the name, “Shishak”, was,

not an Egyptian name at all - or certainly not a pharaonic one - but was one of

those Israelite-applied names in vogue in King Solomon’s court along the lines

of “Shisha” and “Shashak”.

David Rohl,

admittedly, does make a very good fist of trying to match Ramses II with

Shishak. But, as we have read, this ‘new’ version of Shishak runs into some

insurmountable problems, thus placing “the New Chronology … under considerable

threat”.

Rohl, like Peter

James (Centuries of Darkness), still manages to score telling points

against convention, but his mid-way revision leaves him wandering in

something of a no man’s land.

Overall

Velikovsky’s revision (his Ages in Chaos series) has, despite its

flaws, paved the way for relieving ancient history of its troublesome “Dark

Ages” (c. 1200-700 BC).

Moreover, it has

spelled the end of the “Sothic” astronomical theory upon which artificial bed

the lengthy dynastic history of Egypt has been so uncomfortably spread out. Its

worth has become apparent from the plethora of biblico-historical synchronisms

- so lacking in the Sothic scheme - that have sprung up in association

particularly with the Eighteenth Dynasty.

Unfortunately,

some of the best minds associated with the necessary modification of

Velikovsky’s revision, most notably those connected with what has come to be

known as the “Glasgow School” of the late 1970’s to 1980’s - the likes of Peter

James, John Bimson and Geoffrey Gammon - eventually abandoned those

well-established Eighteenth Dynasty synchronisms and went off in search of

their ‘new’ chronologies.

There is an

interesting exchange between one who had persisted with the “Glasgow” findings,

Michael Reade, and Bimson, formerly of that school, who had not (C and C

Review 1999:2, pp. 38-40):

FORUM

A further synchronism

between Palestine and

Egypt by Michael G.

Reade

Ten potential synchronisms

between Palestine and Egypt during the period 1000-600 BC (approx.) were listed

in the article ‘Shishak, the kings of Judah and some synchronisms’ [I]. A

further such synchronism can be derived from John Bimson's article 'Dating the

wars of Seti I' [2]. This one has the special advantage of being independent of

Dr. Velikovsky's proposals in Ages in Chaos [3], which dominate the

first four of the ten synchronisms and which seem to be particularly distrusted

by some people. Dr. Bimson's article rather plainly shows that Seti I's

campaigns in Palestine were synchronous with the time of Jehoahaz (of Israel).

Jehoahaz ruled Israel during years 23-37 of Joash of Judah … though he is

elsewhere credited with 17 years of rule (II Kings 13: I). ….

Notes and references

Reade, MG, 'Shishak, the Kings of Judah and some

synchronisms', C&CR 1997:2, pp. 27-36.

Simson, Dr J, SISR V:l, pp.

11-27,1980/81.

Velikovsky, Dr I, Ages

in Chaos, Abacus (pub. Sphere Books), 1973, first pub. 1952 in USA.

…”.

A response to Michael

Reade

by John J. Bimson

Michael Reade is leaning

heavily on my 'Dating the Wars of Seti I' (SISR V:I, 1980/81, pp.

11-27), written almost twenty years ago. He goes so far as to state that my

article 'rather plainly shows that Seti I's campaigns in Palestine were

synchronous with the time of Jehoahaz (of Israel)'. Unfortunately I no longer

stand by the conclusions of that article and want to state clearly why I do not

believe any further arguments should be based on it. A little history may help

to clarify the picture.

By the late 1970s it became

obvious to a number of us who were testing Velikovsky's chronology that his

separation of the 18th and 19th Dynasties was not viable. However, at that

stage we were still persuaded that his redating of the 18th Dynasty

had a lot to be said for it. The next logical step was therefore to test the

possibility of adopting Velikovsky's dating of the 18th Dynasty and letting the

19th and 20th Dynasties follow it consecutively (as in the

conventional scheme). This experiment was reflected in some of the papers

presented at the SIS international conference held in Glasgow in 1978 [I] and

consequently the alternative revision became known as the 'Glasgow Chronology'.

The paper to which Michael Reade refers was an attempt to test and develop that

revised chronology.

However, doubts about the

Glasgow Chronology soon emerged. On the Egyptian side, we could not find room

to accommodate the Third Intermediate Period; in my own field, the archaeology

of Palestine, it became clear that sufficient compression of the Iron Age would

be difficult to achieve; Peter James's work on the Hittites raised parallel

problems; and so on ... After

further research and soulsearching, those of us most closely engaged with this

problem (myself, Peter James and Geoffrey Gammon) reluctantly admitted that our

alternative to Velikosvky's scheme could not be brought to completion. In short,

the evidence was now forcing us to question Velikovsky's dating of the 18th

Dynasty. Hence the postscript (dated Oct. 1982) which Peter James added to his

Glasgow paper shortly before its publication: 'The writer would like to add

that he now feels somewhat higher dates than those experimented with in this

paper are required by the evidence'. ….

Notes and References

See

papers by Geoffrey Gammon, John Bimson and Peter James in Ages in Chaos? Proceedings of the Residential

Weekend Conference, Glasgow, 7-9 April 1978 (SISR VI: 1-3), 1982. …”.

I have, like M. Reade,

found myself still continuing favourably to embrace “Glasgow” modifications

despite the fact that its authors would no longer associate themselves with

their early findings. And I have also, similarly to Reade, written of the

“Glasgow” school as having ‘thrown out the baby with the bathwater’ - for Reade

will, in his response to Bimson, use the like phrase, ‘thrown in the sponge’:

Michael Reade replies

I am happy to assure Dr Bimson

that I still stand by what I wrote in C&CR 1997:2 (top of p. 33):

'I shall not attempt to adjudicate the extent to which either Velikovsky's

proposals or the 'New Chronology' are 'right' or 'wrong'. I doubt whether it is

even possible in the present state of the evidence'. My immediate object is to

test the proposition that the founders of the Glasgow chronology may have

thrown in the sponge before it is really necessary.

…. At the risk of being

condemned to be burnt at the stake as an incorrigible heretic, however, I am

willing to test the possibility of major revisions of this pattern, which could

indeed permit this compression. Dr Bimson and his friends betray their own

timidity in this respect when they speak of bringing down the chronology of

Egypt by 250 or 350 years. This implies a shift of the existing order (en

bloc) - a logical impossibility - whereas what I am envisaging is gross

interference with the traditional order, which looks to be a house of cards

erected on insecure foundations. It is high time these foundations were

re-examined but this will obviously be a long and a slow business, involving

testing a great many scenarios which must at least start out as very

speculative. …”.

I fully agree

with Reade’s sentiments, if not his own personal efforts at historical

revisionism. Whereas Velikovsky had proposed - in what is now appearing more

and more to have been a rather flawed reconstruction - that Hatshepsut’s

contemporary, Thutmose III, was the biblical “Shishak king of Egypt”, who

sacked the Temple of Yahweh in Jerusalem in the 5th year of king

Rehoboam (I Kings 14:25), according to the ‘New Chronology’, ably led by David

Rohl, Ramses II of the Nineteenth Dynasty was this Shishak. With Velikovsky’s

anchors of Hatshepsut/Queen Sheba and Thutmose III/Shishak now thrown away, the

‘New Chronology’ immediately suffers from its not being able adequately to

replace these Eighteenth Dynasty candidates with suitable Nineteenth Dynasty

ones. This is especially true in the case of the Queen of Sheba - there is

simply no appropriate royal woman to take her place!

Pharaoh’s

Campaign against Jerusalem

“The

topographical facts have been verified on the spot by a highly competent

scholar …

H.

H. Nelson, … whose only adverse criticism was that the narrowness of the road

had

been somewhat exaggerated”.

Sir

Alan Gardiner, Egypt of the Pharaohs.

Professor

Breasted’s preconceptions

Gardiner, here

on p. 192, is referring to Thutmose III’s First Campaign, undertaken

in his Years 22-23, after Hatshepsut had passed away.

No wonder, then,

if this was Gardiner’s reading of H. Nelson’s view - not to mention that of the

pharaoh’s officers - that Egyptology is such a mess.

Gardiner was

rather more accurate when he famously lamented (on p. 222): “What is proudly

advertised as Egyptian history is merely a collection of rags and

tatters”.

I wrote this when I was

fully in favour of Dr. Danelius’s view that the Aruna road taken by pharaoh and

his army in the First Campaign was actually a road leading directly to Jerusalem.

I have discussed this and its topographical aspect in “

Biblical “Shishak king of

Egypt”, in which article I finally - and

rather reluctantly - departed from my acceptance of Dr. Danelius’s

reconstruction.

Professor James

Henry Breasted considered the warlike Eighteenth Dynasty pharaoh, Thutmose III,

to have been “the Napoleon of Egypt” (Ancient Times, I, Ginn and Co.,

1914, p. 85). And it is to that pharaoh’s records that we now turn, because

they concern Breasted and his reconstruction of the so-called “Battle of

Megiddo”.

Thutmose III has

been confidently dated according to the ‘Sothic’ scheme of things to the C15th

BC. So, the majority of historians would not quibble with Breasted’s bold

conclusion that Thutmose III’s First Campaign occurred during

April/May of 1479 BC. According to Breasted, Thutmose III, in his Year 22,

embarked upon a military expedition into Syria, in order to fight against a

coalition of Syrian princes under the leadership of the “King of Kd-šw”, who

had revolted against Egypt.

Kd-šw

has been identified as the city of Qadesh, or Kadesh.

Pharaoh Thutmose

III emerged from this campaign with a great victory and immense spoils from the

conquered territories. Dr. Eva Danelius (“Did Thutmose III Despoil the Temple

in Jerusalem?”, SIS Review, Vol. II, No. 3, 1977/78, pp. 64-79), tells

of this and of the very poor condition of part of the Egyptian Annals:

A hieroglyphic text, carved

into the wall of a famous and much frequented Temple about 3,000 years ago,

does not survive undamaged. And this is how Breasted described it when he

started working on it around the turn of the century:

"They [the Annals]

are in a very bad state of preservation, the upper courses having mostly

disappeared, and with them the upper parts of the vertical lines of the

inscription." ….

Detailed information about the

length of the various gaps is provided by Sethe, who worked on a critical

edition of the Egyptian original during the same years that Breasted worked on

its translation into English. Gaps noted by Sethe vary from a few centimetres

to more than 1.75 metres! …. In addition, even the signs which remained were

sometimes damaged and their reading open to question. Add to this the enormous

difficulty of translating an Oriental text into a European language which

differs from it fundamentally in its vocabulary, syntax etc. and its evaluation

of events, and it will be understood how questionable all these translations

actually are. No wonder, therefore, that the more important of these inscriptions

induced every new generation of Egyptologists to try and produce a more

complete rendering of the original.

Another pitfall for the

translator is the licence to fill gaps not overly long with words which might

have stood there, according to his - very subjective - ideas. Such words might

have been taken from similar inscriptions where they have been preserved; or

the translator/interpreter simply counts the number of missing

"groups" and tries to fill the gap as best he can with fitting words

of a similar length. Though these insertions by the translator have to be put

in brackets as a warning to students, it happens only too often, especially

when provided by a famous teacher, that in the end they are treated with the

same respect as the original.

….

For Breasted, the

identification of the fortress [My-k-ty or Mkty]

conquered by Thutmose with Biblical Megiddo was a fact not to be doubted. And

his interpretation of the - very fragmentary - text was determined by this

fact. …”.

Dr. Danelius has

done some marvellous critical work whilst following the First Campaign of

Thutmose III through the eyes of professor Breasted. She will point out some

glaring discrepancies along the way, leading to her introduction of Harold

Nelson and his doctoral thesis with its own criticisms of the conventional

scenario. I take up Danelius’s account, adding my own comments here and there.

Let us commence at the beginning:

The story, as told by

Breasted, starts in the 22nd year of Pharaoh's reign, "fourth month of the

second season", when he crossed the boundary of Egypt (Records, §

415). There had been a rebellion against the Pharaoh in the city of Sharuhen,

known from the Bible: the city had been allocated to the tribe of Simeon,

inside the territory of Judah (Josh. 19:6). Nine days later was "the day

of the feast of the king’s coronation", which meant the beginning of a new

year, year 23. He spent it at the city "which the ruler seized", G3-d3-tw,

understood to be Gaza (§ 417) (33). He left Gaza the very next day 16

in power, in triumph, to overthrow that wretched foe, to extend 17"the

boundaries of Egypt, according †[… L.P.H.: conventional representation

of brief Egyptian form for “(may he have) life, prosperity, health”, an

honorific customarily applied to the Pharaoh. – Ed.] to the command of

his father the valiant†18 that he seize. Year 23, first month of the

third season, on the sixteenth day, at the city of Yehem (Y-hm), he

ordered [GAP - one word] 19 consultation with his valiant troops ...

(§§ 418-420)

….

The attentive reader will have

observed that there is no gap in the middle of line 18. Nevertheless, Breasted

inserted before the words "at the city of Y-hm" in brackets:

"(he arrived)" (§ 419). In his History of Egypt he goes much

more into detail: "Marching along the Shephela and through the sea-plain,

he crossed the plain of Sharon, turning inland as he did so, and camped on the

evening of May 10th (34) at Yehem, a town of uncertain location, some eighty or

ninety miles from Gaza, on the southern slopes of the Carmel range." (pp.

286/7)

Not a word of all this appears